It was like a Ph.D. student Dionna Williams realized fundamental flaws in the way medical science treats people who have HIV and also use illegal drugs or misuse prescription drugs.

People in this group often have worse outcomes than people with HIV who do not use these drugs. Drug use and addiction have been linked to faster HIV disease progression, a higher viral load, and worse symptoms, including brain-related problems.

For years, many doctors and scientists believed that these poor outcomes resulted from people not taking the antiretroviral therapies that keep HIV under control, says Williams, a neuroscientist now at Emory University in Atlanta. No one really tested that hypothesis, however—in part because people who report substance abuse were often excluded from HIV clinical trials.

The argument made no sense to Williams, who met HIV patients during a summer program while working on their Ph.D. at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. “Every person with HIV who has a substance use disorder can’t all be off their medication. Everyone can’t help but go to the doctor. This is not possible.” Even people who take their antiretroviral drugs regularly have bad results if they also use cocaine, for example. Perhaps there are biological reasons why HIV, its treatments and illegal drugs are such a bad mix, realized Williams, who uses the pronouns she and they. Their careers have been devoted to exploring these connections.

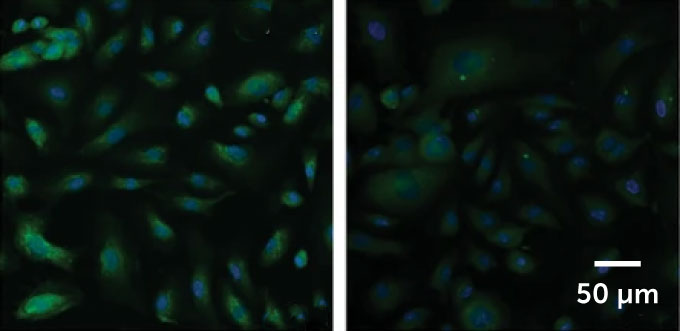

Earlier this year, for example, Williams and colleagues reported in CNS fluids and barriers, that in human cells in the lab, cocaine increased the ability of one anti-HIV drug to cross the brain’s protective barrier, while decreasing the ability of another. The team found that cocaine can also increase the amount of enzymes needed to convert the drugs into their active forms.

Such findings suggest that the problem is not always that people who use illegal drugs are not taking their prescriptions, but that they may need higher or lower doses or a different treatment.

Williams’ research includes those who are marginalized and excluded in part because Williams understands what it’s like to be an outsider.

“I own multiple marginalized identities. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone in science who is like me,” says Williams. “I am a non-binary black woman. I’m weird too. I am autistic. I am [a] the first generation [college student]. I am from a disadvantaged background.” Williams is also a single parent, martial artist and dancer.

Holding all those identities has helped Williams understand people of all kinds and be a better scientist and mentor, they say.

“She’s just an amazing young researcher,” says Habibeh Khoshbouei, a neuroscientist at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, noting that Williams’ research fields — pharmacology, neuroscience and immunology — are diverse.

Perhaps most impressive is that Williams uses human cells and samples from people, says Khoshbouei. Most researchers, including myself, use laboratory animals such as mice or rats to study the brain and immune system. Laboratory animals have carefully controlled diet and living conditions. They are genetically similar. All this makes it easier to interpret the results of the experiments. Working with people and their cells requires addressing all the ways people change, and often requires hundreds of participants. But it is human differences that Williams wants to understand.

“The level of complexity and commitment and openness to working with actual human samples is beyond measure. It’s not comparable,” to working with animals, Khoshbouei says.

By working directly with human cells, Williams also bypasses the need to translate findings from animals. This means the findings may be more likely to stick.

A recent study—on how drugs affect the body in general—helps illustrate why results in humans don’t always match findings from animal studies. Williams and colleagues probed the bodies of rats, mice and rhesus macaques for the activity of 14 genes that produce proteins that detect cannabinoids, the active compounds in marijuana. Rodents and monkeys are often used as adjuncts to humans in medical studies, including studies looking at the potential health benefits of medical marijuana.

For animal studies to be useful, results must be comparable across species. But when the team looked at rodents and monkeys to see where chemical-sensing proteins — called endocannabinoid receptors — were located in the animals, the patterns didn’t match.

The mice made detectable levels of one of the main endocannabinoid receptors in their colon, kidney, spleen and visceral fat, the team reported Feb. 26 in Physiological Reports. Mice produced it mainly in the kidneys and colon, while macaques produced it in the spleen and visceral fat. There was even variation between individuals within a species. “Nothing is the same,” Williams says. “If we don’t understand that, we won’t be able to make good therapies.”

Similarly, some people may make too much or too little of the drug-sensing protein in certain organs, Williams says. Many scientists will dismiss the change as noise. “That’s not hype,” Williams says. “It’s really important information about human biology.”

Williams is “fearless,” says Gonzalo Torres, a neuropharmacologist at Loyola University Chicago’s Stritch School of Medicine. “She is not afraid to go into research fields [in which] she is not necessarily an expert.” Torres directs mentoring programs including the MINDS program for various junior faculty in the neurosciences, in which Williams participated.

Williams stands out for being smart, strategic, creative, tenacious and tenacious, Torres says. “She’s hungry, she wants to know, she wants to follow.” And Williams works hard to develop the skills and knowledge needed to answer their research questions. “Each time she’s going deeper, and going deeper, she grows and her research team grows. She’s becoming a superstar,” says Torres.

Williams credits their autism with helping “to connect the themes in a very interdisciplinary way.” Autism allows them to see beyond social norms and structures, they say. “We think differently. We see the world differently… When people say ‘It can’t be done,’ [I say]’Well, why not?’ Or ‘Nobody’s watching it, ‘Why not?'”

#HIV #illegal #drugs #bad #mix #scientist #unexpected #reason

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org